Tom Kundig’s father was an architect, but early on he wasn’t interested in this as a path for himself. He always felt closer to the natural world via science, yet it lacked the poetry he craved. He eventually decided to go into the profession after all. He did realize that one of his favorite outdoor activities had much in common with the field. “Mountain climbing was also a way into architecture for me, there are a lot of parallels,” he explains. “It’s not just about getting to the top, it’s about the elegance in how you get there.”

Sculptor Harold Balazs was an influential mentor to young Kundig, who spent hours at his home and shop in Mead, Washington. Watching the artist experiment freely boosted his own confidence and fostered his ability to embrace risks, which is integral to his life and work today.

Tom Kundig \ Photo: John Nakatsu, courtesy of Olson Kundig

Kundig joined Olson Kundig in a previous iteration and became an owner of the firm in 1994. As a principal, he explores the relationship between people and their environments, from built to cultural. Always deferential to a structure’s surroundings, his architecture is quietly powerful and connected to the human experience.

He also envisions various gizmos which reveal the wonders of physics within the natural world, crafting tactile moments that are often forgotten in today’s digital overload. Whatever the project, Kundig collaborates with artisans and engineers to challenge design conventions while continuing to evolve his practice.

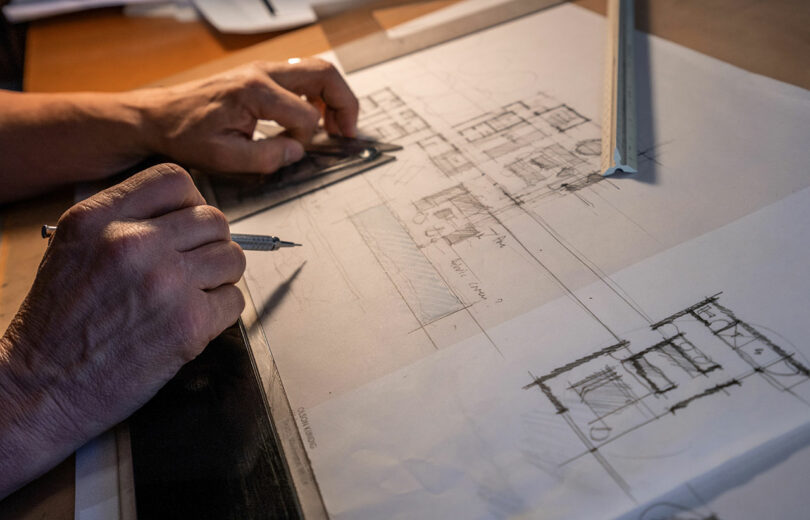

With so many ideas floating around at any given time, Kundig prefers to capture them the analog way and put them down on paper. “For me, drawing is a way to solve a problem, and the hand is the most direct link to the brain,” he notes. “It’s a communication tool, it’s a design tool, it’s everything.”

Today, Tom Kundig joins us for Friday Five!

Photo: John Nakatsu, courtesy of Olson Kundig

1. Seal Sculpture by Luke

I bought a small sculpture when I lived in Anchorage, Alaska in the 1980s, carved by an Iñupiaq artist named Luke from up north in Kotzebue. The sculpture is a seal, carved from a geological core – natural stone that carries its own deep history. It’s one of the most nuanced, beautiful pieces I’ve ever come across. There’s a quiet honesty in it, you can feel the clarity and sensitivity of the maker, even though his life was marked by extreme hardship. The women who owned the shop didn’t really want to part with it; it was clear that Luke meant something to them. Every time I see that sculpture, I think about him – about that raw, uncompromising landscape he lived in, and how something so small can hold so much of that world inside it.

Photo: John Nakatsu, courtesy of Olson Kundig

2. Cowboy Hat by Ritch Rand

My cowboy hat was handmade by Ritch Rand, and it’s one of those objects that feels deeply personal. Designed and crafted specifically for me, it fits beautifully on my head like it was always meant to be there. When I put it on, it connects me back to my life in the high desert – to the forests, rivers, and open landscapes that have shaped so much of my life. I’m not a cowboy, but the hat reminds me of that rugged, honest way of living close to the land. It’s a functional object, but it’s also a thing of beauty, and for me, those two qualities are inseparable. I only wear it in the high desert landscape. Real beauty comes from function, from something made to do its job well – and this hat does exactly that.

Photo: John Nakatsu, courtesy of Olson Kundig

3. Jeep Wrangler

My Jeep Wrangler, built by American Expedition Vehicles, effectively represents what I value most: adventure and purpose. It’s made for a reason – to go anywhere. Long distances, short distances, into the urban city center, into the mountains, onto the shore, into the landscape, into adventure. Every time I see it, I smile, because it represents the ability to explore, to be curious, to get lost and then find your way back. It’s also a purposely beautiful object – its beauty comes directly from its function. That’s what makes it iconic.

Photo: James O’Mara

4. The Pencil

For me, the pencil is literally the link between the thought and the page – or napkin… whatever is immediately handy. There’s something so incredibly powerful about a simple, tactile tool that you can just carry in your pocket. You can sketch and edit, you can communicate, explain things, draw things – and you don’t even need batteries.

5. Maquette Sculpture by Harold Balazs

This small white sculpture is one of seven maquettes Harold Balazs made near the end of his life. They carry an ethereal quality, as if caught between what’s finished and what’s still becoming. The genius of Harold’s art is that it intentionally leaves space for interpretation. He never prescribed meaning to his work, and that openness is what made it powerful.

Harold had this rare ability to merge art, craft, and life into one continuous experiment. When I was a kid, he told me: “If you want to see what art can be, look at hot rods.” To him, the hot rod was an inspirational phenomenon – a pure expression of rebellion against conformity. Their craft was an incredible source of inspiration for his work, one that left a lasting impression on me.

Now, this maquette sits in my studio. A subtle wink and nod to Harold’s humor, curiosity, and relentless drive to make things – a reminder to carry forward that spirit of audacious creativity that he embodied so authentically, and so unapologetically.

Works by Tom Kundig and Olson Kundig:

Photo: Simon Devitt

TE WHARE TUPU KIRIKIRI

North Island, New Zealand

Te Whare Tupu Kirikiri – the house growing from the sand – is a modern interpretation of the traditional modest beach hut. This coastal sanctuary along New Zealand’s North Island appears to emerge from the dunes, designed to endure harsh coastal conditions while deepening connections with the surrounding landscape.

Photo: Yoshihiro Makino

MANHATTAN BEACH RESIDENCE

Manhattan Beach, California

On a narrow sloping site just blocks from the ocean, Manhattan Beach Residence draws inspiration from the honest expression of structure and utilitarian design approach characterized by California’s mid-century modern architecture, mixed with the client’s active outdoor lifestyle. The design complements the eclectic architectural language of the surrounding stucco, wood-framed and mid-century homes, incorporating large awnings and proportionate massing, while retaining its own distinct expression in the dense urban neighborhood. This 5,310-square-foot residence terraces the hillside in a series of volumes, creating a puzzle of interconnected zones flowing through the topography. Varying degrees of opacity and transparency preserve privacy while maximizing views and natural light in a challenging urban infill context.

Photo: Magnus Marding

DALARÖ HOUSE

Dalarö, Sweden

Located in one of Stockholm’s prime holiday destinations, Dalarö House creates a summer retreat that is sensitive to the surrounding landscape. Gently nestled into the hillside, the home is approached from above via a flagstone pathway, acting as a waypoint in the journey to the water and docks below.

Photo: Aaron Leitz

MAXON STUDIO

Carnation, Washington

Complementing an existing home, also designed by Olson Kundig, Maxon Studio is a dedicated office for the client’s creative branding agency, providing space for both production and quiet reflection. The two-story steel tower is mounted on a 15-foot-gauge railroad track, allowing it to transition from a nested extension of the home’s living space to an independent, detached studio. Maxon Studio reflects the materiality and views of the original home, while translating the home’s horizontal proportions to a vertical arrangement. This contrast creates a dialogue with the existing building as well as a new experience of the heavily wooded site.

Photo: Tim Bies, courtesy of Olson Kundig

ROLLING HUTS

Mazama, Washington

Responding to the owner’s need for space to house visiting friends and family, the Rolling Huts are several steps above camping, while remaining low-tech and low-impact in their design. The huts sit lightly on the site, a flood plain meadow in an alpine river valley. The owner purchased the site, formerly a RV campground, with the aim of allowing the landscape return to its natural state. The wheels lift the structures above the meadow, providing an unobstructed view into nature and the prospect of the surrounding mountains.

Photo: Aaron Leitz

THE PIERRE

San Juan Islands, Washington

The owner’s affection for a stone outcropping on her property and the views from its peak inspired the design of this house. Conceived as a bunker nestled into the rock, the Pierre, the French word for stone, celebrates the materiality of the site. From certain angles, the house – with its rough materials, encompassing stone, green roof and surrounding foliage – almost disappears into nature.

Photo: Nic Lehoux

COSTA RICA TREEHOUSE

Santa Teresa, Costa Rica

Costa Rica Treehouse is inspired by the jungle of its densely forested site on the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. Built entirely of locally harvested teak wood, the retreat engages with the jungle at each of its three levels: the ground floor opens to the forest floor, the middle level is nestled within the trees, and the top level rises above the tree canopy with views of the surf at nearby Playa Hermosa beach.