A few months ago, I was lying in bed, lightly clutching my phone, when Instagram Reels presented me with a brief video that promised an impossible soap opera: There were animated cats—with feline faces but unmistakable human bodies—living seemingly human lives, including in a human-seeming house and also, for some totally unclear reason, at a seemingly human construction site. There was drama: A female cat appeared to have been knocked up. There was also, somehow, a related love triangle involving two far more muscle-y male cats vying for her affection. None of the cats actually spoke. Yet somehow the plot proceeded, with one cat winning the heroine’s heart. It was well rendered. It was brain-meltingly inane.

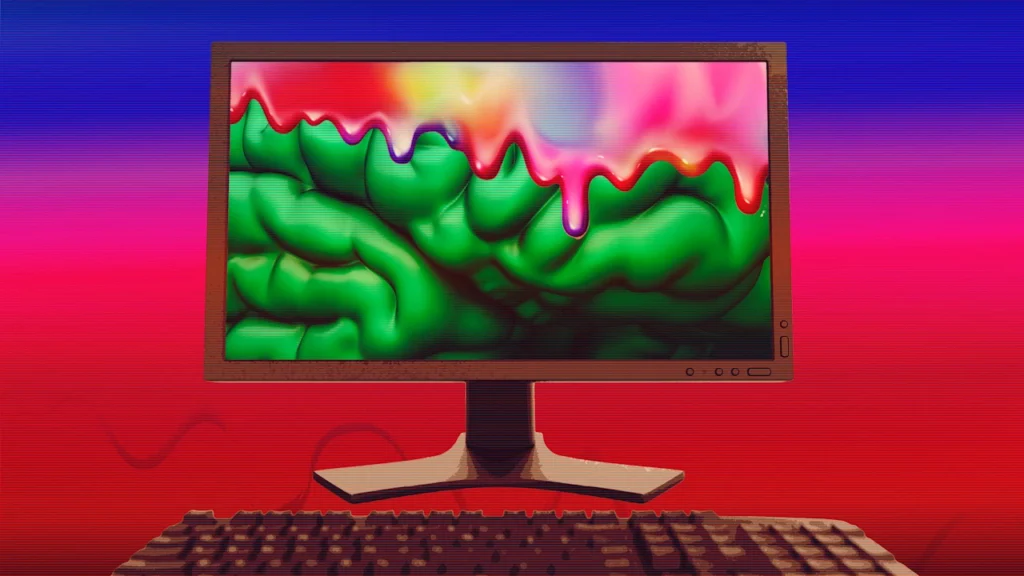

AI slop is now our collective shorthand for short-form digital garbage. Specifically, the term slop evokes liquidy, wasteful goo, threatening to gush over everything. We use this description because the content AI is manufacturing is often low-quality, vulgar, stupid, even nihilist. What decent defense can be mounted for the video I just described, at least to the best of my internet-corroded memory? This output is gross, indeed, sloppy. And it’s getting everywhere.

AI slop did not emerge from artificial intelligence, generally. (Artificial intelligence has a broad scope, but the term has been around for a few decades and is often associated with machine learning.) Specifically, the term was birthed around 2023 in the aftermath of generative AI, when platforms like ChatGPT and Dall-E became publicly available, according to Google Trends. All of a sudden, everyday internet users could generate all sorts of stuff.

While AI companies sort out a business model—they’re working on it!—the internet public has been left to navigate a subsidized AI free-for-all, where we can render slop into existence with merely some keyword cues and a chatbot. Of course, with mass production comes surplus and, then, refuse. We containerize actual trash because otherwise debris gets on everything else and makes everything less good. AI is, arguably, doing the same on the internet. It’s clear we think of a lot of AI as trash, though we’re not doing much to clean it up.

There are already clear signs of contamination. The arrival of low-cost AI generated content has obviated a certain category of digital parachute journalism: stumbling upon a wacky or concerning online trend, then quickly writing it up without any form of verification. Fox News recently published an attempt at such internet stenography—during the shutdown, designed to denigrate Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) beneficiaries—only to later issue a clarification after the outlet learned the videos were created by AI. The confusion goes the other way, too: While reading a clue, Jeopardy! host Ken Jennings recently caught heat for describing something as AI generated when, in fact, it wasn’t.

The quagmire has even gotten the billionaires. In the aftermath of Zohran Mamdani’s victory in New York City’s mayoral election, financier Bill Ackman shared a video of Elon Musk talking about the mayor-elect. Musk “is the spokesperson. He is brilliant, incredibly articulate, and spot on,” said Ackman of the video, only for the community notes section of X to confirm that the video of Musk was AI. The Notes entry pointed to the video’s producers, who note their channel isn’t actually affiliated with the SpaceX executive.

Deni Ellis Béchard, a senior technology writer at Scientific American, recently cautioned that the challenge of mass-produced cultural content, of course, isn’t new: Innovative technologies always spur new forms of art, but also a largess of worthless bleh. This was also the case with the printing press, the internet, and cinema, he explains. “In all of these situations, the point wasn’t to forge masterpieces; it was to create rapidly and cheaply,” he writes. “But the production of new types of slop widens the on‑ramps, allowing more people to participate—just as the Internet and social media birthed bunk but also new kinds of creators. Perhaps because much of mass‑made culture has been forgettable, original work stands out even clearer against the backdrop of sameness, and audiences begin to demand more of it.”

Indeed, the world of mass AI creation will inevitably feature some true gems. AI masterpieces, even. But there are real, unfortunate consequences of the real getting all mixed up with the fake, even more than it already was. Sure, there are reasons to think that the search for an objective truth is futile. But the alternative is corrosive—and structural—confusion. The risk isn’t that we’ll miss the AI jewels hidden under slop, but that we, ourselves, will drown in it.

We might even be fogging up the digital panopticon. It’s become totally normal to know quite a lot about someone’s life from their social media. But today, my Instagram Reels, at least, is clogged with bizarre—though, it pains me to admit, engrossing—AI videos. These videos are certainly less common on the platform’s classic photo grid, but the platform is pushing us to short-form video, anyway, where this slop flourishes.

Eventually, we’ll reach a tipping point where AI overruns organic human activity on the internet. As Axios observed, the web will shift into a bot-to-bot, rather than person-to-person, platform. This, of course, is hard to measure: The whole point is that bots are trying to impersonate humans.

Still, one cybersecurity firm recently found that 51% of the internet is now generated by bots. Last year, an analysis published by Wired found, over a multiweek period, that 47% of Medium posts appeared to be generated by AI. The company’s leadership seemed totally fine with this, as long as people weren’t reading the stuff.

But even if we aren’t reading the trash, it’s still introducing a new source of duplicity to our collective online knowledge. Eventually, also, the same confusion will come for the machines. A study in Nature published earlier this month found that AI can struggle with significant attribution bias. Even worse:

“We also find that, while recent models show competence in recursive knowledge tasks, they still rely on inconsistent reasoning strategies, suggesting superficial pattern matching rather than robust epistemic understanding. Most models lack a robust understanding of the factive nature of knowledge, that knowledge inherently requires truth. These limitations necessitate urgent improvements before deploying LMs in high-stakes domains where epistemic distinctions are crucial.”

Companies have built powerful facial recognition by slurping up images of faces posted on social media to train detection algorithms. AI faces might complicate this methodology, though. A few months ago, FedScoop reported that Clearview AI, a dystopian operation that scraped hundreds of millions of images from social media to build a highly accurate facial recognition model and then sell that technology to the government—was hoping to build a deepfake detector.

LinkedIn recently announced that it’s now using data from its site for improving Microsoft’s generative AI models, though much of the site already sounds like an AI bot (Is it? We don’t have a way to measure!). AI companies have explored using synthetic data to train AI systems—a reasonable strategy? Perhaps, in some contexts. But it also seems like a bad idea.

In fact, there are tons of concerns about AI contaminating itself. There’s serious worry about a phenomenon called model collapse, for instance. Another Nature study last year found that “indiscriminate use of model-generated content in training causes irreversible defects in the resulting models.” There’s the possibility of creating an AI feedback loop, corrupting the very real and “very true” human data that was supposed to, in aggregate, make the technology so powerful. Amid the unctuous praise lobbied toward AI firms, slop seems like a problem for them, too.

The nightmare scenario is something like the Kessler Syndrome, a fancy coinage to describe how humanity is polluting outer space. In low-Earth orbit, space trash (including a lot of dead satellites) frequently hits other trash, powerful collisions that then produce even more space trash, making the entire place cloudier and much harder to navigate and use. A similar future could await artificial intelligence: a whack-a-mole hodgepodge of AI creations and AI detections, all trained on increasingly AI-polluted data.

When you get sloppy, you blur your words and start to stumble. AI may be similarly fallible.