If you’ve seen a bird’s-eye view of Earth over the past decade, chances are it came from Colorado-based Maxar Intelligence. From some 280 miles up, its powerful imaging satellites have created an atlas of modern problems: the impacts of extreme weather, the build-up of Russian tanks near the Ukrainian border, the ruination of Khartoum and the decimation of Gaza, even the not-so-total destruction of Iranian nuclear facilities by U.S. bombers.

What you may not have noticed: Last month, the Maxar brand was itself wiped out, after its private equity owner replaced it with a new moniker: Vantor.

The new name reflects how the company that sees everything on Earth now sees itself. Peter Wilczynski, Vantor’s chief product officer, points to “the harsh V, which gives it that edge.” The edginess extends to a slick new website, where fast-paced scenes on screens evoke Jason Bourne, or Alex Karp. But unlike Palantir, where Wilczynski spent a decade, or Anduril, a Vantor partner, the new name does not come from The Lord of the Rings, the touchstone for so many unabashed defense tech firms. Still, Wilczynski admits: “it could be Elvish.”

The Maxar makeover “reflects a broader crossroads for Earth observation,” says Jarkko Antila, the CEO of Kuva Space, a Finnish startup building a constellation of AI-equipped hyperspectral nanosatellites, capable of monitoring any material on the Earth’s surface. “Raw satellite imagery alone is less of a differentiator. Combining imagery with AI-powered analytics and sensor fusion to access real-time actionable intelligence is what customers demand.”

The hard-edged, tech-forward revamp isn’t just marketing. Maxar’s transformation reflects bigger shifts in the business of watching Earth. A new wave of military and intelligence demand has led companies to double down on government work or even enter the market for the first time. According to Novaspace, a consultancy, the data and services market for defense and intel customers grew by 42% over the past five years, reaching $2.2 billion in 2024. National security work now represents more than 65% of the whole earth observation data market.

Whereas imagery satellite companies once leaned into civic applications, the firms are increasingly turning to AI to rapidly analyze all kinds of space data, and sharpening their focus on national security amid turmoil here on Earth. “We’re experiencing growth across every region as customers respond to the changing geopolitical climate,” Wilczynski says. Vantor’s international business has grown by double digits this year to around 100 government and corporate customers, with the bulk of its contracts now with military and intelligence agencies, he adds.

A separate Maxar division that builds the satellites, the California-based Maxar Space Systems, was also rebranded, as Lanteris. At the top of its new roadmap, the company said it was centered on “platforms for missile tracking, secure communications, and resilient constellations that safeguard U.S. and allied interests.” Last week, the lunar infrastructure firm Intuitive Machines bought Lanteris for $800 million, “mark[ing] the moment Intuitive Machines transitions from a lunar company to a multi-domain space prime,” CEO Steve Altemus said in the company’s press release.

Investors who previously shied away from national security are now pouring in record amounts of cash. According to Bain & Company, venture capital investment in defense tech has increased more than eighteen-fold over the past decade. Over the next decade, Goldman Sachs estimates, the global satellite market will grow from $15 billion to $108 billion. “DoD is basically saying, ‘Hey, private sector, spend your equity dollars, do some preliminary work and that will help us decide what we want,’” Shahin Farshchi, a partner at Lux Capital, said October 29 at a satellite conference in California.

A data glut

At Maxar—Vantor—the makeover was years in the making, says Wilczynski. In 2022, the private equity firm Advent International purchased Maxar Technologies in an all-cash $6.4-billion transaction in 2022 and split its imagery and satellite businesses into separate divisions. Advent—whose business involves buying, repackaging and selling companies—said the firms would prioritize work for the U.S. government and its allies as part of its broader defense portfolio. Since then, Maxar Intelligence has shaken up its executive team with tech veterans and rejiggered its business, with a focus on services and extracting insights from data.

Vantor—which grew partly out of the early Google Maps partner DigitalGlobe—also operates ten satellites built by Maxar and another ancestor, GeoEye. Its six WorldView Legion satellites produce some of the highest-resolution color images commercially available, down to 30 centimeters, or 15 with “enhancement”—good enough to count individual tanks and the crowns of trees. (Only Airbus’s satellites offer a comparable resolution.) Dozens of other companies operate some 1,200 earth observation satellites, helping governments and companies keep tabs on everything from airbases to mines to big box parking lots in a zoo of formats, from optical to hyperspectral to SAR and RF.

All this adds up to a problem of too much space data, more than humans can look at, let alone sort, combine, or usefully analyze. “It’s like a thousand times, a million times, the data that you were handling 10 years ago,” says Wilczynski, who previously helped develop Palantir’s data management system and geospatial platform.

The glut has pushed Maxar and its two large earth observation rivals, Planet and BlackSky, to become more like tech firms, building AI to combine data from space and other domains like drones and phones, and devising slick interfaces that can extract objects and flag changes on Earth and at sea. (Years ago, a similar flood of video evidence—and the subscription services involved in managing it—led the law enforcement contractor Taser to hire executives from Tesla and Apple, build a cloud-based platform, and rebrand as Axon.)

Incumbent players are only now moving into the world of rapid data fusion, says Antila of Kuva, which plans to sell defense customers subscription-based access to its hyperspectral microsatellites; on-board Nvidia chips will help speed up data processing. “But it remains to be seen how quickly they can reset their existing processes and business models.”

At Vantor, that effort has meant a range of new partnerships and products, from analysis tools to near-real-time 3D globes, to less traditional ways of presenting and selling geospatial data. Ninety percent of Vantor’s revenue now comes from subscriptions and recurring contracts, amounting to over $900 million, a business the company projects will grow by double digits this year.

“Geopolitics are driving countries to want eyes faster”

In part, the shift can be traced to a set of color images taken by Maxar on November 1, 2021. The photos, first published in Politico, showed tanks massing near the Ukrainian border. That, and subsequent Maxar imagery, helped convince the world that Putin was serious about his plans to invade, more than three months before it actually happened.

The war that followed was another reminder that commercial space data wasn’t just a nice-to-have. Along with communications provided by Spacex’s massive Starlink network, commercial satellites would prove pivotal for Ukraine’s defense: Since images by Vantor and other companies are unclassified, U.S. and NATO commanders and analysts could easily share them with Kiev, providing critical intelligence.

That sharing arrangement became well known in March, after President Donald Trump abruptly turned off Kiev’s access to a Maxar-run digital atlas used by the Pentagon and other US agencies and overseas partners. The White House restored access 11 days later, but the episode unnerved U.S. allies around the globe.

“The moment was a wake-up call for partners around the world, and we’ve seen an uptick in demand from international government partners who want to pay for direct access to our spatial intelligence capabilities,” says Wilczynski.

The push for more surveillance from space is said to be existential in the longer term, too. For defense and intelligence agencies facing the prospect of AI-powered weapons and drones, the data that comes from above will determine who wins future wars.

“Geopolitics are driving countries to want eyes faster,” Will Marshall, CEO of Planet, told a panel at World Space Business Week in September. The publicly traded company has signed deals with NATO, Germany, and Wales. It has also announced a new factory in Berlin, and seen its stock more than triple this year. “People are very worried, and countries want to have their own independent means of surveying the world,” he said.

Since July, Vantor has signed over $300 million in contracts, including a deal with Taiwanese aerospace firm AIDC for Raptor, a system that uses its 3D terrain models to guide swarms of drones. Under a separate Army contract, Vantor is also building a 3D virtual globe for training and planning. Last month, the company also signed a deal with the Space Force to capture images of other satellites, a growing concern amid tensions in orbit. Wilczynski puts the market for its products next year at $2 billion.

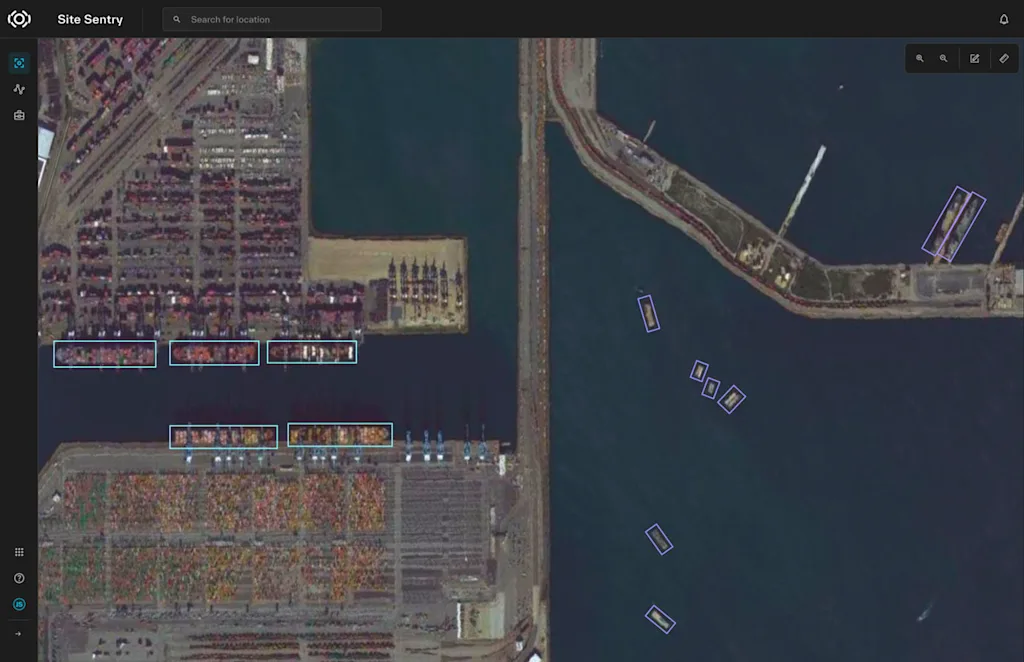

One of Vantor’s largest U.S. government contracts is for GEGD, the web-based portal that provides unclassified imagery and geospatial data to 400,000 users across federal agencies and U.S. partners. The company last year also won a contract to provide AI capabilities for programs that help analysts at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency monitor industrial sites and detect vehicles and ships. That work has informed some of its new commercial AI products.

The shift toward defense represents something of a return to the industry’s roots. The space industry has traditionally been propelled by intelligence agencies, which provide the large stable contracts needed to put expensive satellites into orbit. Over the past decade, Maxar and a growing number of earth observation firms have expanded into civil and corporate applications, including mining, energy, finance, insurance, and disaster relief.

“The public is left out”

But for Vantor and the rest of the industry, the picture of the future is still murky.

As defense budgets explode, U.S. government budgets for civil and commercial contracts are shrinking. The Trump administration’s $18.8-billion budget for NASA, pending Congress’s approval, pushes the space agency to its lowest level since 1961, and cuts nearly half of its science mission funding, or a third of its science portfolio. On the defense side, where the Pentagon is investing in more of its own satellites (including a requested $40 billion for the Space Force), the administration has proposed about $130 million in cuts to its commercial imagery contracts.

In a letter to Congress in June, executives from Vantor and other firms protested the cuts, arguing they would cede U.S. leadership in space. “The decision to abandon America’s vetted and reliable commercial remote sensing capabilities, while adversaries China, Russia and Iran rapidly expand their state-backed Earth observation infrastructure is ironic, shortsighted, and perilous,” says the letter.

The industry’s concerns underscore the gravitational pull of defense budgets, and the reality that demand for space imagery among non-government customers hasn’t been as high as some had expected. “There are only so many government contracts, and commercial demand never lived up to the hype,” Tushar Prabhakar, founder of Orbital Sidekick (OSK), a hyperspectral data company, wrote at Space Republic. “So maybe the real question isn’t about Maxar. It’s how does this industry finally break free of its own gravity well?”

The industry shifts are also raising eyebrows among advocates for public space data.

Commercial and government programs like the U.S.’s Landsat and the EU’s Sentinel have been foundational for climate science, agriculture, and disaster relief for decades. Vantor and other EO companies also run open data programs, providing imagery in the wake of disasters. U.S. and Western governments subsidize some access to commercial data for use by scientific and humanitarian users. Public portals like NASA WorldView, EO Browser, the Copernicus Browser, Google Earth Pro Microsoft’s Planetary Computer, Esri’s Living Atlas, and OpenAerialMap offer tools for searching, sharing, and using various kinds of satellite and drone imagery.

But all of those programs are contingent on goodwill. And researchers have reported significant gaps in the coverage provided by public data. For instance, there is no comprehensive repository of recent or historical high-resolution imagery, which could be valuable for a range of humanitarian and environmental challenges.

As the industry focuses more on the defense and intelligence sector and government budget cuts threaten research satellites, public access to critical data could be at risk.

“That’s my worry,” says Bill Greer, a geospatial analyst who worked on humanitarian mapping at Maxar and founded Common Space, a nonprofit trying to launch its own satellite for research purposes. “A complete enclosure of satellite imagery by defense and intelligence, where the public is left out.”

Seeing the Earth in near-real time

To see how space got here, zoom out a bit.

It was Space Imaging, Maxar’s ancestor, that launched the first spy-grade commercial satellite in 1999, with a then eye-popping resolution of 1 meter per pixel. Since then, a parade of advancements—including SpaceX’s reusable rockets—made it much cheaper for giants and upstarts alike to bring large and small satellites to orbit.

In February, Maxar hit a critical milestone. Six years after a mechanical failure took out one of its costly Legion satellites, it successfully launched two more, Legion 5 and 6, aboard a SpaceX rocket. “If that program did not work,” says Wilczynski, “there was not a company.”

Once the satellites were up, the time was right for the company to go on “offense,” and turn “a lot of the latent potential that the company had into something that’s a little bit more concrete and durable.”

While Maxar was a SpaceX-like “space behemoth,” says Wilczynski, with tentacles reaching across the whole space domain, “we were really trying to think about a company that was more vertically integrated across space, air, and ground, using the space-based data as the global foundation,” he says.

All the data is handled by TensorGlobe, a set of cloud-based technical services built to process an unceasing flow of high-resolution imagery, covering some six million square miles per day.

Wilczynski likens the infrastructure to Amazon Web Services, but for geospatial data, continuously ingesting, stitching, and enhancing. “That’s really valuable for a customer who’s trying to build a spatial intelligence system that takes imagery from multiple providers,” he says.

With a zoo of vendors, combining and making sense of the data at speed is one challenge. “It will be interesting to see how Maxar is going to deal with the interoperability of various data sources and do it in a near-real-time cadence,” says Antila.

Wilczynski agrees. The hurdles for earth imagery now aren’t about hardware, but “an information overload challenge of data coming from each of those domains being pretty siloed, being pretty disconnected,” he says. “And this is something that I was really fascinated about at Palantir, thinking about knowledge graphs and connecting semantic data.”

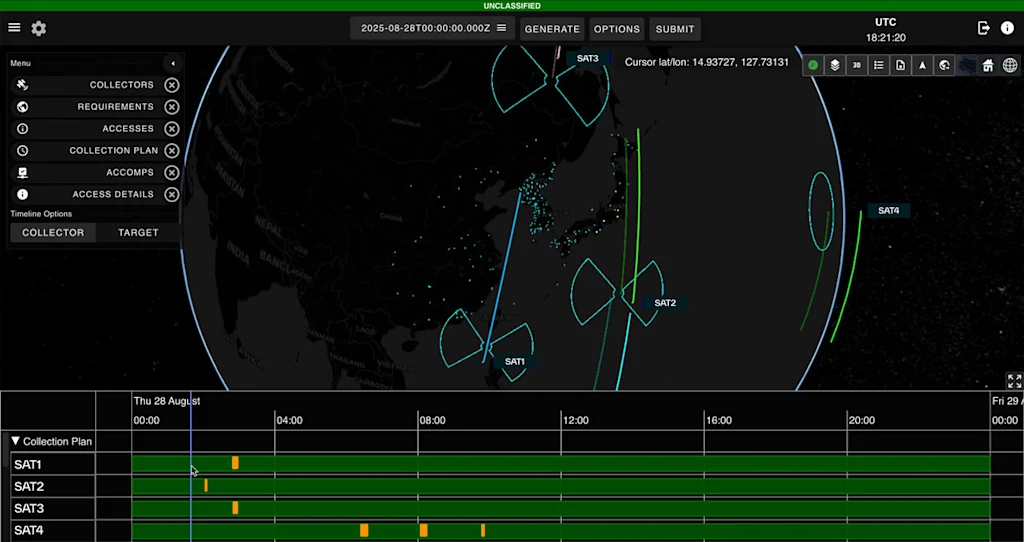

Wilczynski says defense agencies are already using the platform to choose from a mix of government and commercial satellites, just as companies might split their data workloads between their own data centers and cloud services. And as AI models learn from the work of human analysts, the system is helping automate the process too. “That scheduling’s actually very hard,” he says.

So is turning all the imagery into a single 3D map, in near real-time. Other algorithms, from the startup Ecopia AI, layer on 2D vector base maps, with features like building footprints, roads, and land cover. Yet more software wraps a mess of images onto a “living” globe.

These models form the basis of Raptor, a system that helps drones navigate by terrain in GPS-denied environments like Ukraine. They also feed the U.S. Army’s One World Terrain program, which will provide geospatial data for the mixed-reality headset project started by Microsoft and now led by Anduril.

The 3D maps can be continuously enriched and verified against new imagery coming from sensors on helmets and drones. And those “real world” terrain models can then be used to train geospatial AI models, more firmly “grounding” them to prevent dangerous falsehoods in the outputs. Researchers at IBM, Google, and elsewhere have also released dynamic maps and geospatial AI models that have been used by insurance companies and disaster relief groups.

“A lot of how we’re thinking about the risks of AI are, how do you continue to use real world observations to keep the system from spiraling away into some false hallucination of what’s happening by connecting it to the world,” says Wilczynski.

A cloudy picture

Even as the data gets better and faster, the ground is shifting beneath the industry’s feet.

As part of the budget proposal for NASA submitted earlier this year, the Trump administration proposed abandoning more than 40 missions, including at least 14 Earth science missions. The White House has also called for a roughly 30% reduction—about $130 million—in the National Reconnaissance Office’s procurement of imagery under its commercial imagery purchasing program. The administration is also seeking to eliminate funding entirely for synthetic aperture radar imagery, a capability widely used since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In a June 16 letter, the CEOs of Maxar, Planet, BlackSky, Iceye US, Capella Space, and ground systems provider KSAT told the leaders of the House and Senate Appropriations, Armed Services, and Intelligence committees that the budget cuts would undercut Trump’s Golden Dome plans, stall the Space Force’s initiative to create a Commercial Augmentation Space Reserve, and “derail” U.S. leadership in AI development.

Commercial imagery “can be used today, or they can wait six, eight years and spend billions of dollars building systems,” Susanne Hake, general manager of Vantor’s U.S. government business, said at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Global Aerospace Summit in September. “We commercial companies have shown that we can deliver at scale, but in order to do that, we do need long-term contracts and consistent funding in order for us to be able to build our technology.”

Vivid Features vectors in Reynosa, Mexico, including road centerlines and 2D and 3D building footprints

But for Bill Greer, of CommonSpace, the market’s continued reliance on the defense sector comes at the expense of other, less-resourced users. Maxar’s rebrand “looks like private equity positioning for a sale, likely to defense primes or similar players,” he wrote on LinkedIn. “If that happens, we can expect further restrictions on who gets access to this data, price increases to make the more restricted data more profitable, and restrictions on how the data is used. Government will pay more for access to the same data, and end users will miss out entirely.”

Some have advocated for government rules that say any imagery purchased with taxpayer dollars be released to a wider array of civic users. Groups like UN-SPIDER have also pushed for more capacity and training for Earth observation, especially in developing countries.

Satellite companies could also open up more of their archives. If they did, Greer thinks the industry could drive more non-defense commercial business. “This is a big spot where the commercial industry gets it wrong,” he says. “They’re not developing the market without allowing access to that data.”

Sentry integrates Vantor’s Cortex and Forge software to automate multi-constellation orchestration and intelligence analysis.

There’s some historical precedent here. The Landsat program began providing then-precious 60-meter views of Earth in 1972, but its full impact was limited by cost, with prices reaching $4,500 per scene during the 1980s when the commercial sector operated the satellite. In 2008, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) transitioned to a policy of open data, free to users.

The impact was immediate. Daily downloads skyrocketed from 53 scenes to more than 5,700, and within three years, a report found annual economic benefits of $1.7 billion in the United States alone, according to a June report by the Group on Earth Observations (GEO), a partnership of governments and international organizations. By 2023, those benefits had grown to $25 billion annually, far exceeding the $5 million collected in data sales by the USGS. The open data enabled projects like Australia’s water resource mapping, which analysed 300,000 Landsat scenes to grasp continental-scale water trends, and, said GEO, “catalysed a global movement toward open-access Earth observation.”

Greer would like to see the commercial sector follow Landsat’s lead and open up more of its data. “The problem is that this data is super good, and access isn’t,” he says. He adds: “My hope is that you start seeing more of that [data], and then that leads to tasking, and there would actually be growth in the industry, and more people that actually understand the value.”