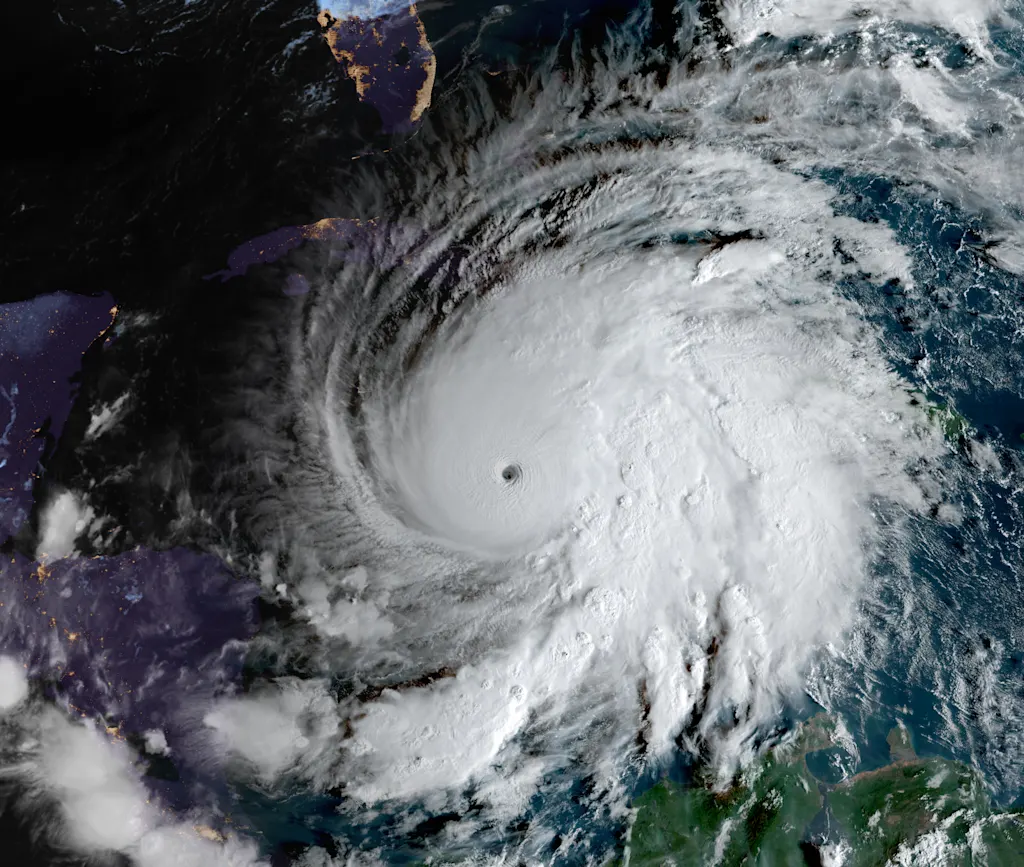

Hurricane Melissa, which made landfall in Jamaica on Tuesday, October 28, was one of strongest hurricanes to make landfall in the Atlantic ocean ever recorded. And it was supercharged by the effects of climate change.

As it approached the Caribbean, Melissa—a Category 5 storm with winds of 185 mph—moved over exceptionally warm waters.

The ocean was 2.2°F (or 1.2°C) warmer than average for this time of year—conditions that were “made up to 900 times more likely by human-caused climate change,” according to the scientists at the research nonprofit Climate Central.

Carbon emissions from human actions trap heat in the atmosphere, but our oceans absorb most of that heat—about 93% since 1970.

As the storm moved over those warm waters, it rapidly intensified. In just 24 hours, from October 25 to 26, its wind speeds doubled from 70 miles per hour to 140—turning it from a tropical storm into a Category 4 Hurricane.

This level of intensification is “at the extremes of what has ever been observed,” according to scientists at Imperial College London.

Then, the hurricane intensified again, reaching Category 5 strength and becoming one of the most powerful hurricanes ever recorded in the Caribbean. It’s an example of the way global and ocean warming, caused by human activity like the burning of fossil fuels, is increasing both the likelihood and intensity of storms.

Climate change made Melissa more likely—and more damaging

In a cooler world that wasn’t experiencing climate change, a hurricane like Melissa would have made landfall in Jamaica once every 8,000 years. But in today’s world, climate change made Hurricane Melissa four times more likely to occur, according to a rapid analysis by scientists at Imperial College London.

Climate change also made Melissa’s wind speeds about 10 miles per hour stronger, according to a rapid attribution study by Climate Central.

And it made the storm more damaging overall. A world without climate change would have seen a hurricane that was about 12% less damaging, per Imperial College London’s analysis.

That difference is relatively small because, as the researchers note, “an event of this severity already causes near maximal damage.” But it still signifies how climate change is making extreme weather events even more destructive.

Preliminary reports put the direct damage from Melissa on Jamaica’s physical assets at $7.7 billion. That’s more than a third of the country’s GDP.

AccuWeather estimates an even more destructive picture: $22 billion for the storm’s total damage and economic loss, including not only destroyed homes and businesses, but tourism impacts, financial losses from power outages, travel delays, impacts on shipping, and so on.

Extreme storms are becoming more common

As climate change worsens—fueled by our continual use of fossil fuels and increasing global carbon emissions—extreme storm behavior like we saw with Hurricane Melissa will become more common, and could get even more intense.

“These storms will become even more devastating in the future if we continue overheating the planet by burning fossil fuels,” Professor Ralf Toumi, director of the Grantham Institute—Climate Change and the Environment at Imperial College London, said in a statement.

“Jamaica had plenty of time and experience to prepare for this storm, but there are limits to how countries can prepare and adapt,” he added. “Adaptation to climate change is vital but it is not a sufficient response to global warming. The emission of greenhouse gases also has to stop.”

The effects of climate change don’t necessarily mean, however, that we’ll see more storms every season, or that every single storm will be this strong.

“Maybe the most important thing to understand about hurricanes in the warming world is that not all of them will be able to take advantage of the raised ceiling from ocean warming, but some of them will, and this one did,” Daniel Swain, a climate researcher at UCLA, told CNN.

“And when we have situations like this, where it happens near or over a populated area that is susceptible to major effects, that the subsequent devastation will have been made worse, significantly worse, by climate change.”