Think about this: have you ever tried to assign a number to your happiness? Where are you, on a scale of 1 to 10, at this moment? A tough question, isn’t it? Your perception of happiness could change depending on whether you just drank a really good cup of coffee or are stuck in traffic. This is the exact situation Bhutan’s well-known philosophy, Gross National Happiness (GNH), aims to capture on a national basis. It is a fascinating case study to show that the success of a country does not always lie in what is in your wallet. So, is GNH something that can really be measured? The answer is as complex as the human heart.

Principles of GNH

GNH is more than just a vague, good-feeling statement. It is a real framework of data founded on four pillars that sound similar to how one might describe a balanced life: sustainable socio-economic development, environmental sustainability, cultural diversity, and good governance. Think of these pillars as the load-bearing structures of a house. However, to determine if the house will be sturdy, it is helpful to check the rooms in the house.

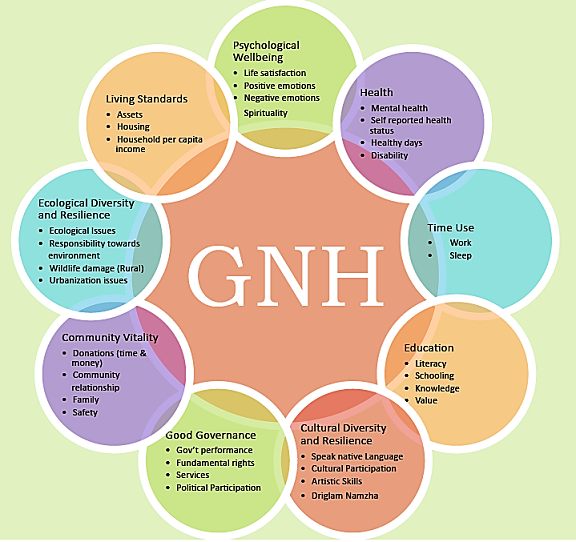

That is where the nine domains come in. The nine domains are the more concrete GNH framework, representing the areas that concern us, from well-being (are you feeling well?) to time use (are you too busy?) to ecological health (is the air that you breathe clean?). Each domain is full of specific, quantifiable statements. For example, a “psychological well-being” score isn’t a random guess. The score is based on your self-reported frequency of feelings of calm, experience, compassion, and generosity. This is a holistic, top-to-bottom assessment of the well-being of a nation.

How is GNH calculated?

Rather than using a simple “happiness score,” GNH utilises a sophisticated approach known as the Alkire-Foster method. The logic is essentially the same one used in counting multidimensional poverty, except in the reverse order. It is not about how “happy” you are at the time, but whether you have sufficiency in certain dimensions of well-being. Have you had enough sleep? Do you feel safe in your neighbourhood? Have you visited any cultural events? Each indicator gets a “yes” or “no” based on the criteria set for each.

I consider you “happy” in the GNH index if you have met the required number of “sufficiencies” across all the dimensions. In other words, if you get to two-thirds of the way, 66% to be exact, you are considered “happy.” GNH avoids the “my 7 is your 9” issue present in simple scales, and it enables a more accurate understanding of what a person might need to create a greater sense of happiness, such as better education or filling gaps in social engagement.

Critiques against the system

Let’s be frank: happiness is a feeling and not a spreadsheet. And this is the most significant area of resistance to the GNH concept. Opponents claim that no matter how thorough the methodology behind measuring happiness is, it cannot mitigate the subjective quality of emotions. The GNH survey, while a clever construct, still depends on the person’s

self-assessment, which can be affected by anything from their mood that day to how they construct the questions. Some academics even criticise the construction of ordinal scales, as they are like claiming you can measure how tall a mountain is with a rubber band.

On the other hand, GNH can and has been used politically. Some pundits have noted that GNH has been an easy escape, or “utopian dogma,” for covering up a painful history and avoiding real-world issues, such as mental health issues and a shell-shocked society. This is a good reminder that a pretty philosophy can come with some warts, too.

Results obtained

Despite this critique, GNH is more than just an academic exercise in Bhutan; it is a core part of the governance of Bhutan, and the people’s happiness is even embedded in the country’s constitution. Every new policy, whether it is a bridge project or a health initiative, has to be considered under a GNH Policy Screening Tool, determining whether it meets the ideals of a GNH country. It is not only the application of the philosophy, but also a fixed step in the policy-making process.

The outcomes are substantial. For instance, Bhutan’s free and universal health care is a result of GNH focusing on happiness and health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Bhutan’s response, which was informed by GNH providing free testing and free treatment, became a success story across the world, demonstrating that being more concerned about collective vitality and well-being leads to better outcomes in pandemics

Conclusion

The purpose of the GNH experiment is fundamentally about asking a different question from the rest of the world. Countries generally focus on a single number—their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Bhutan, however, wants to know if its citizens are really flourishing. GDP only highlights commercial exchanges! GDP counts the costs of cleaning up pollution but doesn’t measure the value of a clean river; it counts the money spent on divorce lawyers but doesn’t measure the joy of a healthy marriage.

Conversely, GNH is an attempt to honestly value the clean river, the vibrancy of culture, and a supportive community. GNH understands that a country can have great material wealth and be spiritually poor. So, while GNH may never be an accurate measure of happiness, it is less about the accuracy and more about the important change in thinking it provides—shifting from measuring what we produce to measuring what is valuable. And in a world that is consumed by growth at any cost, I think that is worth pursuing.

Written by – Deshna J Doshi

The post Gross National Happiness: Metric or Myth? appeared first on The Economic Transcript.