Innovation hubs were once the darlings of corporate strategy, promising to future-proof businesses and spark breakthrough ideas. But two decades in, the cracks are showing. Too many hubs have struggled to prove their worth, and some have quietly shut down altogether.

In reality, these costly spaces never lived up to the hype—and the future lies elsewhere. Rather than investing in shiny new labs, organizations should be cultivating innovation communities: networks of people, inside and outside the company, who collaborate around shared challenges and opportunities.

Looking Back: Proliferation

Innovation hubs have proliferated through private enterprise over the past two decades. This has largely happened because of broader cultural shifts, like the increasing pace of societal and technological change, and globalized competition, which made it imperative that organizations develop their own muscle to shape a leading edge. Companies proved this out through rather dependable profit cycles, which in turn created bandwidth for broader exploration. In fact, now innovation hubs are relatively commonplace: According to research by Indicative, more than 60% of financial services organizations in the U.S. have their own innovation hubs, whereas it is close to 40% for automotive and retail sectors.

These hubs usually exist at varying scales in physical form, with a blend of core team and supporting organizers that lead events programming, project development, and stakeholder engagement. Some of these hubs choose to stay close to the core business, be it adjacent to production facilities or headquarters, like BMW’s Project i-Ventures. Their proximity enables an effortless flow of people and ideas from the core business. Other organizations opt for the periphery, both in terms of location and thematic focus, to develop their portfolio with less oversight, and potentially less distraction from the HQ—such as Google X and Pfizer’s Center for Therapeutic Innovation. For these latter hubs, the emphasis has been on bolder bets that could transform the business in longer time horizons.

The way these hubs manifest their mission vary widely. Some stayed close to the core of product-service innovation, either via venture funding or intrapreneurship challenges. Others worked closer to brand differentiation and storytelling, or even positioned themselves as an employee-value-proposition (EVP) vessel. Within all of this, some have been incredibly refined in their form factor, whereas others opt for the messy maker approach.

Independent from their form, the momentum around hubs served the purpose of bringing the innovation narrative to the boardroom. But we’re now in a broader reckoning moment in terms of what the path forward will be, with contraction and restructuring in businesses leaving the innovation hubs in question. And the closure of Ikea’s innovation hub, Space10, and the struggles faced by giants like Walmart, underscore innovation hubs’ systemic issues around purpose, experience, positioning, and mandate.

On top of that, it’s not easy to recount examples where an innovation hub actually turned a company around. An HBR article sourcing Capgemini shows that 90% of innovation hubs failed to deliver on their promise. This highlights a critical point: merely establishing innovation labs does not guarantee success. A company has to carefully craft the right innovation framework and align necessary resources to truly enable business outcomes through innovation, according to another Capgemini report.

The Three Traps

Innovation hubs are trapped in three sets of strategic tensions of their own making: positioning with respect to core business, the balance between product development and communications, and the balance between internal versus external partners.

When hubs sit too far from the core business, they tend to drift into scattered activities without a clear focus or meaningful links back to the company. But when they sit too close, they get bogged down by corporate rigidity and lose the agility needed to make real progress.

In terms of activity, hubs focusing on tangible product-service innovation struggled when early test versions or products did not gain traction—either because there was focusing too much on desirability or viability, but not both. In other contexts, innovation hubs focused more on marketing, comms and storytelling—and those may have had a boost in the early phases, but in absence of “tangible results,” the energy dissipated over time and was simply framed as “innovation theater.” Here, a good litmus test is the professional background of their Chief Innovation Officers (CIO)—some directly come from product development backgrounds, and others from communications, but rarely bridging both.

A third tension is whether the innovation system focused more on engaging the internal stakeholders in an organization, or engaged with external partners and ecosystem players. While the framing of “open innovation” is used abundantly, companies also struggled to break down the walls and let the partners in, given the competitive nature of the work.

Although these tensions may come natural with any organization, what is clear is that there is a need for a new narrative for the value of Innovation—especially in the hyper-uncertain, post-COVID, recessionary, restructure- around-the-corner environment.

A New Configuration

The provocation is to shift how we think about innovation, away from building more hubs as physical showcases, and toward reimagining how people, resources, and ideas connect across an organization.

What if, instead of drawing hard lines between “the hub” and “the business,” we dissolved those boundaries and allowed innovation to flow more freely across teams and functions?

What if the money spent on shiny new buildings went instead to cultivating relationships: creating open, community-powered networks where employees, partners, and even customers can contribute to problem-solving?

What if, rather than building yet another lab, organizations took stock of what they already have (unused spaces, overlooked talent, dormant partnerships) and reconfigured them into living platforms for experimentation?

And what if innovation became less about a central place, and more about distributed cohorts of changemakers—small, empowered groups connected by digital and physical networks, supported with clear incentives to act?

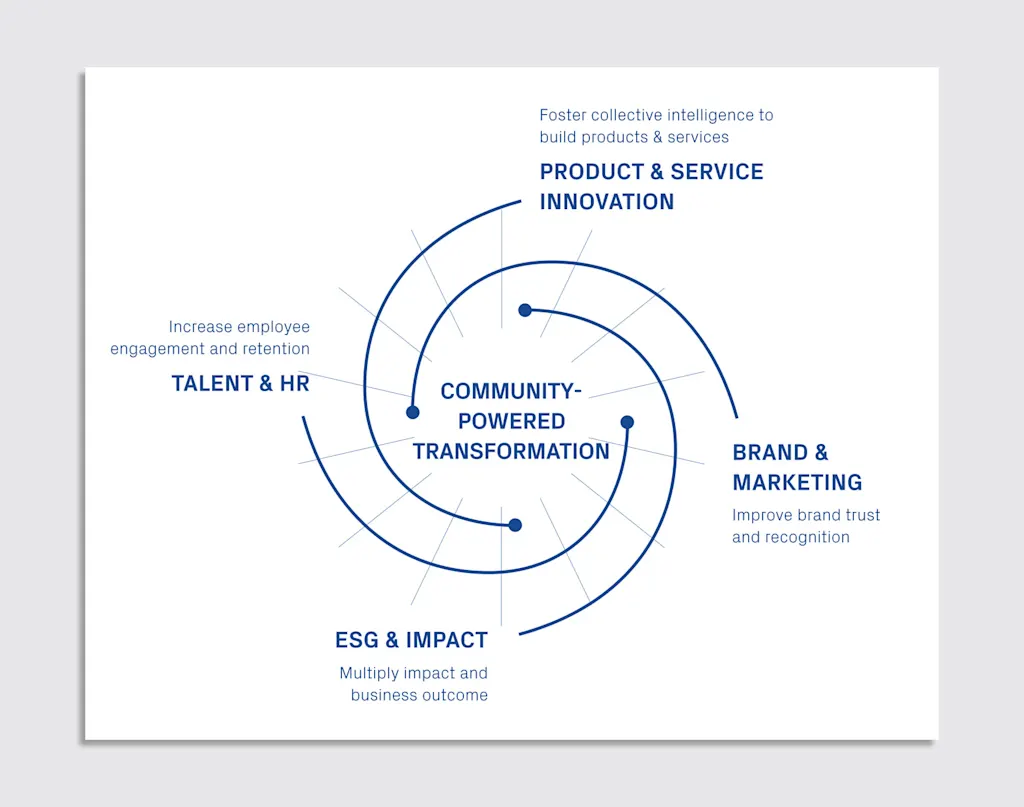

In its highly functioning version, this new path towards community-powered innovation could shift an organization’s DNA across all four key dimensions: product innovation, talent, impact, and brand perception.

Such refocusing would enable the discourse to move away from building physical assets to cultivating innovation communities, acknowledging the slow, arduous but ultimately differentiating act of investing in people and their relationships above all else. In practice, these communities are networks of employees, partners, and sometimes even customers who come together around shared challenges and opportunities. Rather than operating as a single close-knit team, they function as distributed groups that exchange ideas, test solutions, and build momentum across the organization.

This strategy would not only preserve but potentially enhance previous investments, directing organizations toward a future where innovation is seamlessly integrated across the organization.

Innovation & Sustainability as a Shared Agenda

Such a narrative of distributed, community-powered innovation may sound compelling, but it isn’t bold enough for structural change. For that, you need a bigger purpose—and that is the convergence of the innovation and the sustainability narratives within organizations.

Ultimately, the climate crisis is a key challenge that poses an essential risk, alongside massive opportunities. Climate defines a very compelling “why” and can deeply move people. Sustainability can act like a prism that refocuses dispersed efforts, tapping into the energy for key changemakers in organizations that are collaborative and intrinsically motivated, which is exactly the audience that any organization is keen to activate.

Converging innovation and sustainability would also simplify the organizational structures that often create silos or duplicated efforts, making it easier for teams to work toward meaningful results together. In a world where Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and regulation may be taking over the story of sustainability, crafting strong shared narratives can unlock the path for deeper activation.

Ultimately, we need to imagine a world in which each organization defines their “why” in relationship to sustainability, and their “how” in relationship to innovation communities. In that world, organizations powered by communities could move with newfound momentum to drive the change—which is direly needed.

Contributors: Özlem Tuskan, Leen Sadder, Gülnaz Ör, Mert Çetinkaya, Greg Csikos, Melissa Clissold