The early darkness in most of the U.S. means that fall has set in. That also means it’s officially holiday shopping season. With the economic impact of President Trump’s ever-fluctuating tariffs an open question, there’s an opportunity for shoppers to make their spending meaningful, which opens up a lane for companies that are offering something other than the e-commerce onslaught of nearly identical products that populate sites like Amazon and Walmart.

What the Amazons and even Etsys of the world are currently missing is the sense of curation that defines Uncommon Goods, an online shop stocked with exclusive, offbeat items sourced from independent artisans. It’s a cheat code for gift givers—mostly signals, very little noise. Each click is a potential epiphany, connecting me to, say, smartphone-controlled paper airplanes for my nephew, or wooden wall art shaped like a soundwave from my wife’s favorite song. In the age of the Everything Store, it’s a Just the Right Thing Store.

The remarkability of Uncommon Goods’s inventory has helped grow the shop’s revenue at an average annual rate of 25% from 2000 to 2020; it has received more than a million orders per year for the past five years. That je ne sais quoi has often caught the attention of Wirecutter, the New York Times’s product recommendation vertical, which has highlighted many of its wares.

“As gift experts, we spend most of our time scouring the internet, visiting brick-and-mortar shops, and attending trade shows in search of gifts that sit right at the edge of practical and whimsical, with standout quality and value,” says Hannah Morrill, Wirecutter’s gifts editor. “We’ve noticed that Uncommon Goods tends to prioritize unique products from small makers that we haven’t seen before—that’s pretty rare from a large-scale online retailer.”

Of course, as relatively effortless as Uncommon Goods might make holiday shopping, its leadership says that the site’s ever-changing, reliably surprising inventory is the culmination of a tremendous amount of work.

An Uncommon Origin

With shopping, a little lore can go a long way—making some goods seem even better. When an Uncommon Goods artisan has an interesting backstory, those details often make their way into the site’s marketing copy. Shoppers are less likely to encounter the site’s own origin story.

Founder and CEO Dave Bolotsky started his career in the mid-’80s as an analyst at investment bank First Boston. By 1999, he’d become a managing director at Goldman Sachs, where he was due to receive $10 million in stock when the bank went public. Instead, he walked away from the job, leaving that entire imminent windfall on the table. It was just what he felt he had to do.

“I was not bored once in my 14 years on Wall Street, but it felt soulless,” Bolotsky tells Fast Company. “I felt like I was helping the wheels of capitalism spin faster, but not necessarily in a better direction.”

Bolotsky says he got the idea for Uncommon Goods after visiting a Smithsonian Institution craft show. Walking along rows of vendors hawking handcrafted items, he observed how shoppers responded to the personal artisan touch. It raised their eyebrows and spirits as much as it did their inclination to spend money. The only problem was the rarity of such opportunities.

Back then, makers had to act as traveling salespeople, schlepping from one regional show to another. It was all too easy to miss them. The insight Bolotsky had was that if he could take a craft show product, put it online, and sell it 24/7, it might be a huge evolutionary leap forward for retailing, and for artisans in particular.

The challenge? Online shoppers proved stubbornly hesitant. It was the internet’s Wild West era, and trusting one’s credit card details to an online retailer was still considered fraught. When Bolotsky and his team would scout makers at trade shows, it took a lot just to persuade them that the internet was not inherently evil.

He refused to buckle, though, and kept the ship afloat through several rocky, profit-free years. The outlook brightened only after Amazon terraformed the space, Bolotsky admits grudgingly.

“As much as I don’t like them as a competitor, I do admire what they’ve done,” he says. “Amazon Prime was huge in driving online shopping. And to an extent, we ride their coattails.”

One glaring difference between the two, though, is that Amazon has an estimated 300 million to 600 million items for sale at any given moment, while Uncommon Goods hovers around 5,000.

What uncommon goodness actually looks like

The Uncommon Goods site procures roughly 80% of its products through its buying team, while an in-house product development team fills in the remaining 20%, largely through partnerships with a roster of product makers it has worked with before.

Although Uncommon Goods doesn’t chase trends, it often plays in the same sandbox as whatever is popping off in pop culture. When BookTok first exploded, for instance, the product development team rolled out a piece of functional nightstand decor dubbed the Book Nook reading valet, while the buying team sought repurposed book tulips—paper flowers in a paper vase, both created with upcycled books.

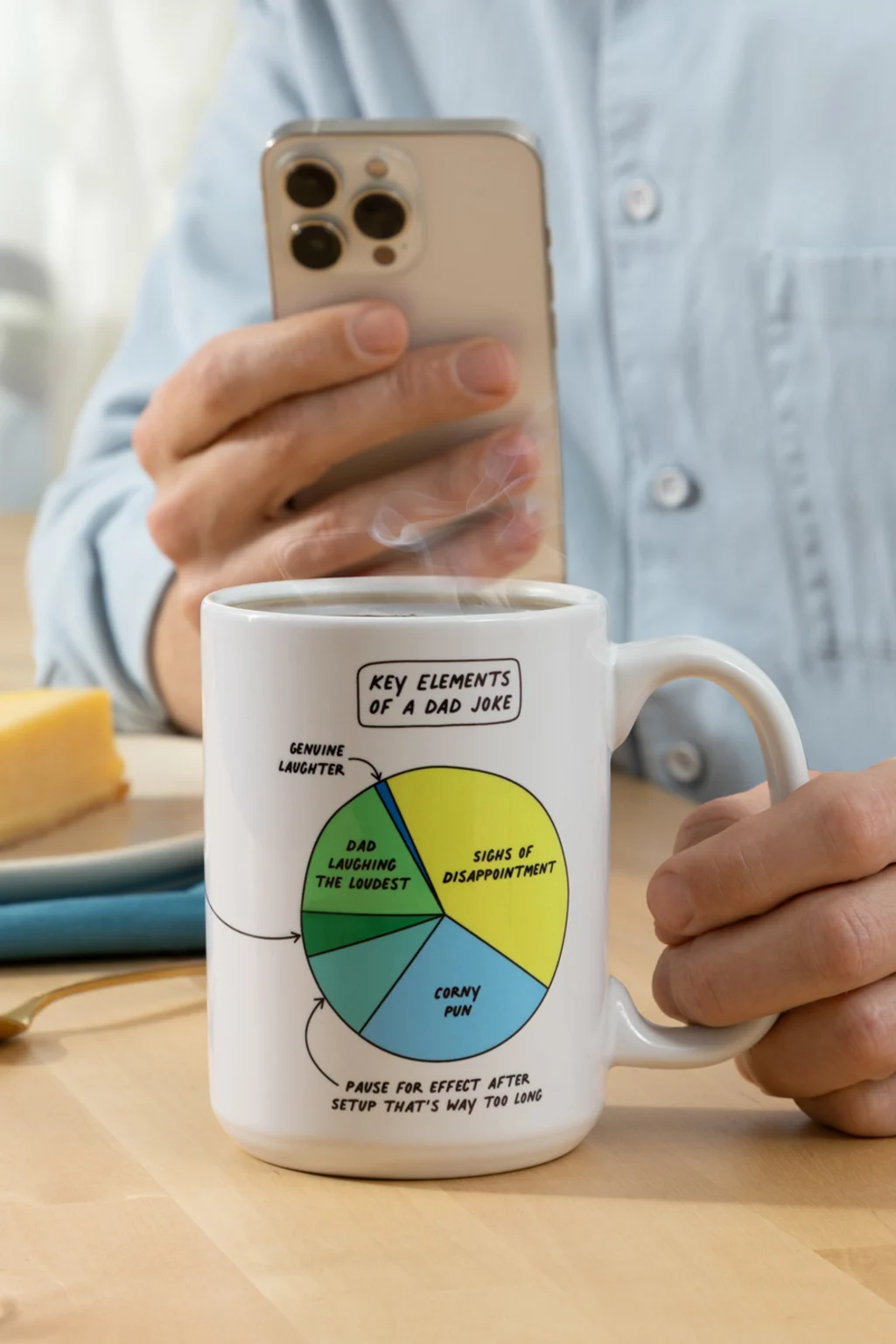

John Berweiler, head of the site’s buying team, says there are a few criteria for what makes a product ready for the site. True to form, it has to be uncommon (ideally something that can join the 40% of the site’s exclusive inventory) and it has to be useful, beautiful, or handmade, but preferably all three. As for the other variables, well, as a SCOTUS justice once famously said of pornography: You know it when you see it.

“Our customers want to win the gift competition,” Berweiler says. “For them, it’s the ‘why’ behind the product. Does it make them smile? Does it make them reminisce about a moment or spark a feeling? That wow factor sets us apart from a frame they might buy at Pottery Barn.”

From idea to hit product

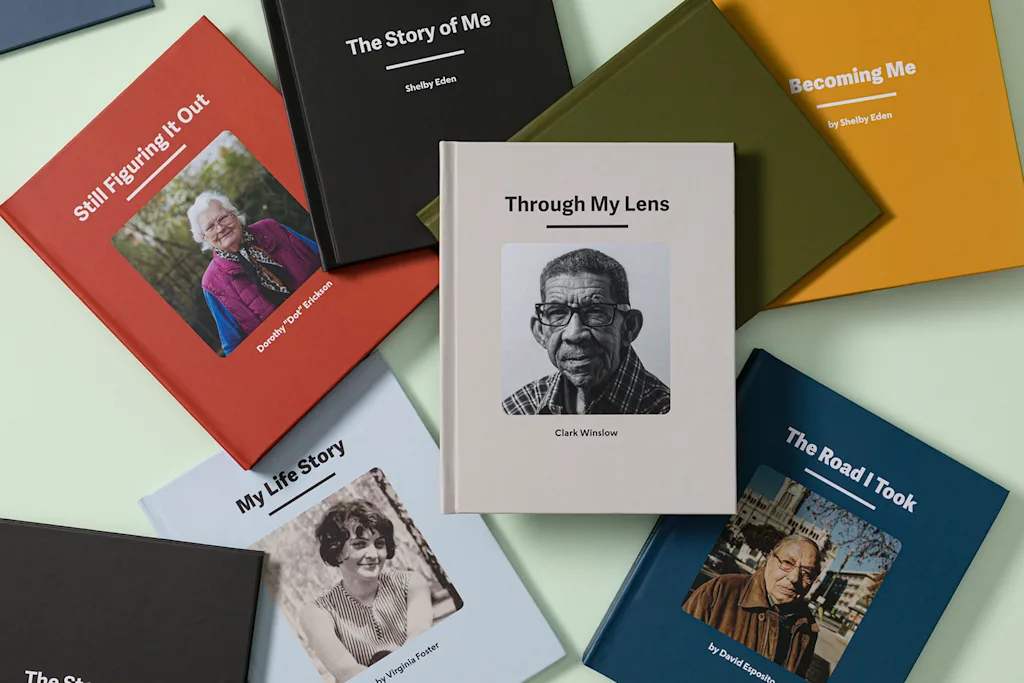

Whenever a member of the buying team comes across a promising item they request a sample. Every Tuesday afternoon, the team gathers for a sample meeting that serves as an America’s Got Talent-like revue, in which each item competes for potential inclusion in the shop. If there’s a winner, or multiple winners, a gauntlet of other considerations follows, spanning from price to exclusivity, and whether the maker has a backstory worth featuring on the site.

Some products developed in-house come out of brainstorming sessions. Bolotsky himself is responsible for more than a few, including a line of interactive mugs with QR codes on them. Other Uncommon Goods items are collaborations between the buyers, product development, and various makers. Last year, for instance, the buying team was looking for new ideas for dining and drinking items, right as limoncello surged back into fashion, and landed on making dedicated limoncello glasses. The team reached out to potter Maggy Ames, who ended up producing an adorable set of ceramic tumblers with grippy thumb divots and elegant hand-painted lemons.

Though the artist was initially skeptical, the limoncello cups blew up. They sold so well that she couldn’t keep up with demand. That’s when the product development team stepped in to scale production on the cups, working closely with the original maker to ensure she was comfortable with how the new product turned out. Through a manufacturer in Thailand, the cups are now made on a larger scale, but can still be hand-painted—keeping their artisan aura alive.

It’s a microcosm of how the company expanded from Bolotsky’s apartment to an operation with 144 year-round employees, all while elevating makers and maintaining the core promise.

Gift-giving in the time of tariffs

Although the buying team is already strategizing for Christmas 2026, first the company will have to get through this year’s holidays, which promise to be more challenging than usual.

The president’s chaotic and aggressive approach to tariffs throughout 2025 has kept American retailers who work in the global marketplace in a bind.

Bolotsky isn’t especially worried, though. About half of the products Uncommon Goods sells are made domestically, he says, and the rest are spread throughout 10 countries, keeping the company less dependent on Chinese-made products than many of its competitors. For the imported products, Uncommon Goods has been negotiating with vendors to meet at least halfway on the pricing or margin hit the company is poised to take. In some cases, Uncommon Goods ended up sourcing products elsewhere; in others, it has taken selected price hikes.

“My biggest concern is actually that, because we sell discretionary products, and because there will likely be greater inflation across the board this holiday season, people may have less discretionary money to spend on gifts that we sell,” Bolotsky says.

If people do end up having less money to spend on gifts this year, they may indeed have to be more discerning about what they buy. Perhaps enough of them will gravitate toward a shop that’s more discerning about what it sells.