The biting chill of the art world’s toxic sociality has a certain way of getting underneath the skin. The short film “It’s Just a Fucking Opening” (2025) goes there and lingers, shivering. The protagonist of the film — which was produced by Jupiter Magazine and debuted at the Chicago International Film Festival last month — is a young, emerging artist named Anisa (played by Ireon Roach). The crucible of her big opening night throws her relationship to those around her — and to her own art — into a crisis of faith.

The film begins in the midst of Anisa’s opening, just after she has given a performance which we never see on screen. We only hear it recounted by a group huddled together in the gallery, where they level critique after vicious critique upon the artist’s work behind her back. (Later in the film, we realize that she overhears the entire thing.) Meanwhile, Ines (played by Camille Bacon), Anisa’s best friend who also curated the show, spends the evening chasing after powerful stakeholders in the art world while ignoring Anisa’s visible sense of anxiety and alienation. And the artist’s partner Yasmine (played by Richele Brainin), who is herself a rising star in the field, misses the opening, leaving a disappointed Anisa skeptical of her relationship and wary of the various pressures that the art world brings to bear on it. All of this pushes Anisa to the edge of a breakdown, and by the end of the film, it is clear that her opening night was never really hers.

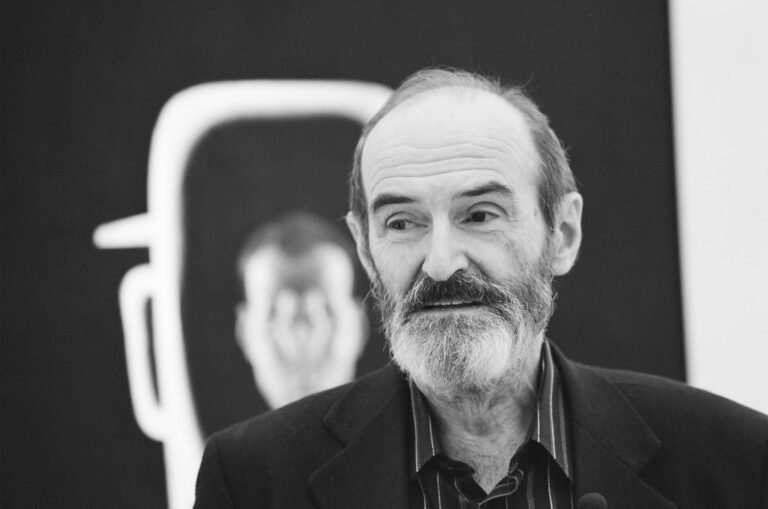

Hyperallergic spoke with the film’s three co-directors, Jupiter Magazine co-founder Camille Bacon, scholar Youssef Boucetta, and artist josh brainin, about the experiences that influenced this piece, centering relationships over ambition, and the criticism — both public and private — that shapes the art world.

Hyperallergic: The ebbs and flows of friendship are vital not only to the internal world of the film, but also to its production: Before you three had a professional relationship, you were close friends. How does your friendship in the real world interact with the friendships depicted in the film?

Camille Bacon: Because we came into this as friends, we were, from jump, very fierce protectors of one another’s ideas and emotional worlds. We got to deepen — through the act of making the film — our fluency in the language of one another’s interiority. Now that the film has been released, I’m invested in protecting not only josh and Youssef’s hearts and spirits, but also the collectively authored documents that are born from our exchange. I’ve never made a film before. This collaboration became an impetus to study the form. josh and Youssef gave me a gift that can only be presented by people who love you: They knew I had something to offer the project before I knew myself, and they ushered me into that belief.

H: And what about the specific intersection of friendship and the art world?

Youssef Boucetta: The art world today is dominated by a commercial ethos, and that’s what we’ve been trying to respond to by considering our relationships in themselves as a possibility to do something artful. There’s also something really interesting when you’re making a film that has a lot of similarities to the worlds you live in in real life, and where the kind of relationships that you depict have parallels to real life. There might have been, at times, fears that what was happening in the film was being reproduced in real life. And so it gave us the opportunity to address that head-on, to actually find a language for friendship through finding a cinematic language that depicts precisely what should not be done in a space where collaboration, intellectual pursuits, and creative pursuits come together.

josh brainin: Yeah, I resonate with that. I’ve always wanted to work with Youssef and with Camille. But having witnessed how things can crumble without care, I didn’t want to put pressure on making a film before I felt like we could understand each other’s needs as the primary engine and not just the collab. And then naturally it kind of just spawned that, like, okay, these are all our passions in different ways. So let’s work together. I also really enjoy the conceptual framework of us as a trio. Youssef as an academic, me as an artist, Camille as a writer.

H: At the opening of the film — and then again at its end — we encounter these armchair critics remarking on Anisa’s work, mostly talking shit about it. How is the film dealing with the question of criticism and what criticism is, or can be, today?

CB: That sequence was entirely improvised. We didn’t give [the actors] much context around what exactly it was they were critiquing because we didn’t stage the performance on set. The fact that all of them were able to — with no practice or rehearsal — slip so easily into the scene says a lot about where we are: skilled at performing criticism. Our friend said that the only thing he didn’t feel was accurate about the film was that the critique happened in the gallery where the artist could overhear it. Typically, these are opinions we take home and share behind closed doors. Part of my mission with Jupiter Magazine, which exec-produced the film, though, is to experiment with contexts where critique can be shared and engaged in real time, which involves accepting a risk. The film was, in a sense, a rehearsal of that aim.

H: There remains a relative dearth of critical publications dedicated to Black art and artists, though of course Jupiter has done so much to fill that lacuna. How does the film deal with the matter of criticism as it pertains specifically to Black art?

jb: I didn’t really want to lean into the respectability politics involved in keeping things “woke” in media, which I feel can limit the humanity, the emotional range of characters, and make them into tokens. I just wanted to see people talking critically about a person’s work, and they just so happened to be Black, you know?

H: The critics in the scene walk a very tenous line between criticism and plain old gossip. How does the film negotiate that distinction?

YB: The characters talk about each other a lot, they take jabs at each other. So the kind of cutting mechanism of thought that they’re whipping around isn’t simply aimed at the work, but at everything around them. And there’s something uncaring about it, but there’s also something really indiscriminately fair about it, where it’s like, “I’m gonna take in these different realities that touch me and process them through the same machine.”

H: The film also opens with a sort of epigraph, a quote from Toni Morrison: “I am suggesting we must pay as much attention to our nurturing sensibilities as we do to our ambition.” Can you speak more about this idea and how it’s working in the film?

CB: In the annotated bibliography in the zine which we made to accompany the film, we wrote that Morrison’s quote is “the nervous system around which we assembled our film’s body.” It became a sort of guiding force throughout the delicate navigation that is working with your friends, and it drew us closer to the inner tension in our protagonist’s dynamic. We watch Anisa and Ines sacrifice their “nurturing sensibilities” in favor of their “ambition,” which threatens their friendship and Anisa’s relationship with Yasmine.

H: You brought up the gorgeous zine you guys made and the annotated bibliography within it. Can you all speak more about what references the film is pulling from, whose voices it’s colored by?

YB: It was really important to us to cite references beyond film, and to consider that what comes first is an impulse to make something, to represent an idea or a feeling, and what comes second is the choice of medium. We cite a DJ set by Crystallmess. There’s also Chris Marker’s La Jetée, which is itself trans-disciplinary: It’s photographic, it exists as a book, but it’s at heart a film and made by someone who’s known as a filmmaker.

jb: Another important reference is the films that are being restored through Milestone Films and Maya S. Cade: These are mostly independent films by Black women filmmakers, stuff that I wasn’t exposed to in high school or undergrad. It was cool to have the opportunity to witness those films, to take them in, and to reference things that have been buried away for a long time.

CB: We all saw Drylongso and Losing Ground, for example, and those two films in particular galvanized us to make a film that’s posing similar questions from a different vantage point. It felt really important to cite both Cauleen [Smith] and Bridgett [Davis] in the zine. I feel tremendous gratitude because I got to watch these films as a 20-something-year-old. I wish I got to watch them as a teenager and now, because of Maya Cade’s work, that’s going to be possible for future generations. We needed to celebrate that in the zine. More broadly, the zine speaks to the importance of a citational ethic, which we want to weave through everything we make. There are a number of texts that make cameos, including the catalog from Koyo Kouoh’s show When We See Us, Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism, and Tom Lloyd’s Black Art Notes. We filmed in the library at Tala Gallery, which was founded by our friend Francine Almeda. The casting process was also culled directly from the social architecture of our actual lives; we included people we love to think alongside. We’re in pre-production for our debut feature, which has already been such a glorious chance to deepen that approach to casting.