The Coral Triangle is a biodiversity hot spot. At least for now.

More than 600 species of coral grow in this massive area straddling the Pacific and Indian Oceans, stretching from the Philippines to Bali to the Solomon Islands. But as the oceans get hotter, coral reefs—and the ecosystems they support—are at risk. Experts predict up to 90% of coral could disappear from the world’s warming oceans by 2050.

Research institutions are racing to preserve corals, and one strategy involves placing them in a deep freeze. By archiving corals in cryobanks, biologists can buy time for research and restoration—and hopefully stave off extinction.

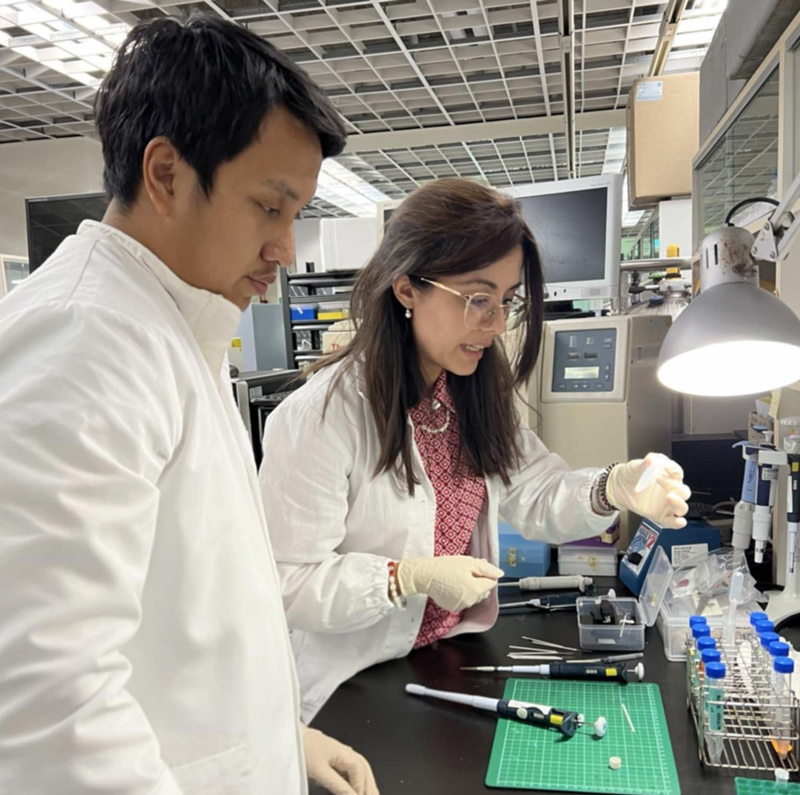

A new capacity-building project is training cryocollaborators in the Coral Triangle region, starting at the University of the Philippines (UP).

The initiative is “very, very urgent,” said Chiahsin Lin, a cryobiologist who is leading the project from Taiwan’s National Museum of Marine Biology and Aquarium.

Room to Grow

“We don’t have that much time to develop the techniques.”

A cryobank is like a frozen library. But instead of books, the shelves are lined with canisters of coral sperm, larvae, and even whole coral fragments chilled in liquid nitrogen.

Coral cryobanking can aid in coral preservation and future cultivation. But the process is tricky and time-consuming and requires trial and error. The temperature and timing that work for one species won’t carry over to others. Plus, it can take 30 minutes to freeze a single coral larva, said Lin.

While materials from hundreds of species have been frozen, very few larvae have been successfully revived and brought to adulthood.

“We hope more and more people can be involved in this research,” Lin said. “We don’t have that much time to develop the techniques.”

The new project aims to increase the number of trained professionals who can freeze the world’s corals. UP’s Marine Science Institute is currently working to open the first cryobank in Southeast Asia. Lin has visited UP multiple times to train researchers on cryopreservation and vitrification. The UP team also traveled to Taiwan to work with samples in Lin’s lab.

The project will establish future cryobanks in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia as well. Those teams will also participate in similar trainings to reach a shared goal: a network of coral cryobanks in the Coral Triangle.

Pausing the Clock

A major benefit of cryopreservation is that it pauses the clock. Some coral species spawn for only a few hours or days each year, and that window changes by species and by region. If a lab group misses the release, they may wait months before collecting materials again.

By freezing coral samples, researchers have more opportunities to experiment throughout the year.

In the past, Emmeline Jamodiong, a coral reproduction biologist in the Philippines, led coral reproduction trainings for stakeholders across the country. Logistics were complicated. People needed to travel from different regions and islands, but “we had to wait for the corals to spawn before we could conduct the training.” Now, even if it’s not spawning season, researchers could still work with coral reproduction.

A local cryobank “offers a lot of future research opportunities,” she said. “I’m very happy that we have this facility established in the Philippines.”

Freezing for the Future

The new project in the Coral Triangle is a helpful addition to cryobiology, said Mary Hagedorn, a senior scientist at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute who developed the field of coral cryobanking.

“A real bottleneck for this field is there’s so few people that are trained as cryobiologists,” said Hagedorn. Every effort to expand the research ranks is valuable.

But cryobanks are just one part of coral conservation, she said. Aquariums that cultivate live coral are also important. Secure storage is essential to keeping samples safe from storms and power outages. Sustained government funding is needed to keep coral frozen and make sure staff are continuously trained.

“Without starting this project, there’s no hope for coral reefs.”

Some coral populations are already functionally extinct, making global collaborations like the one between Taiwan and the Philippines key.

“No one person can cryopreserve all the species of corals in the ocean,” Hagedorn said. Lin’s team has “a wonderful opportunity to get some amazing species and genetic diversity.”

Hagedorn’s international collaborators think it may take 15–25 years to collect enough coral larvae to ensure genetic diversity for a species. Many corals still need a tailor-made recipe for freezing and thawing if they’re going to be cryobanked at all. It’s a daunting task and a tight timeline available to only a handful of institutions around the world. The Coral Triangle network will add to that number.

“Without starting this project, there’s no hope for coral reefs,” Lin said. Coral cryobanking “gives tomorrow’s ocean a better chance.”

—J. Besl (@j_besl, @jbesl.bsky.social), Science Writer

Citation: Besl J. (2025), A cryobank network grows in the Coral Triangle, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250451. Published on 5 December 2025.

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.