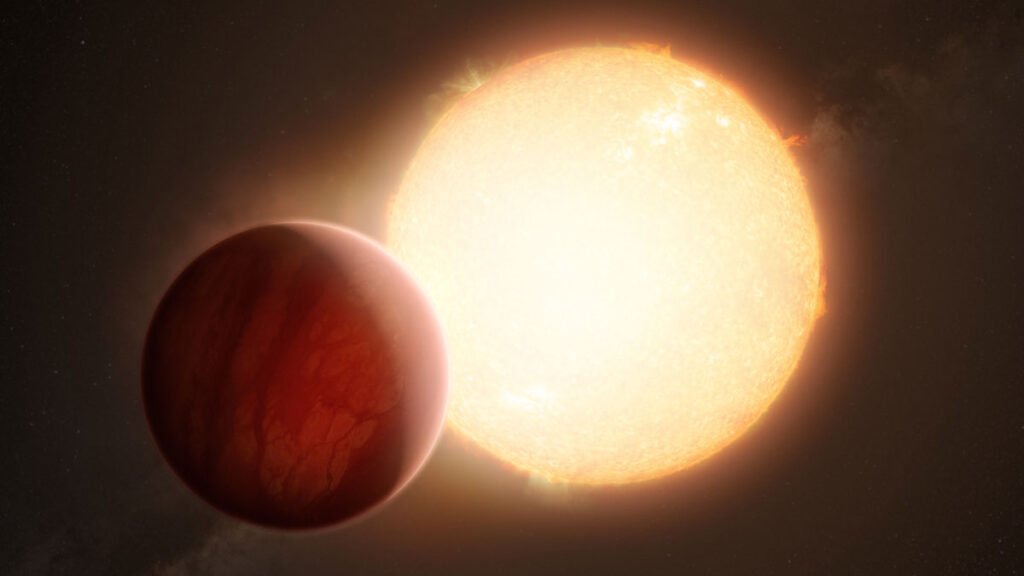

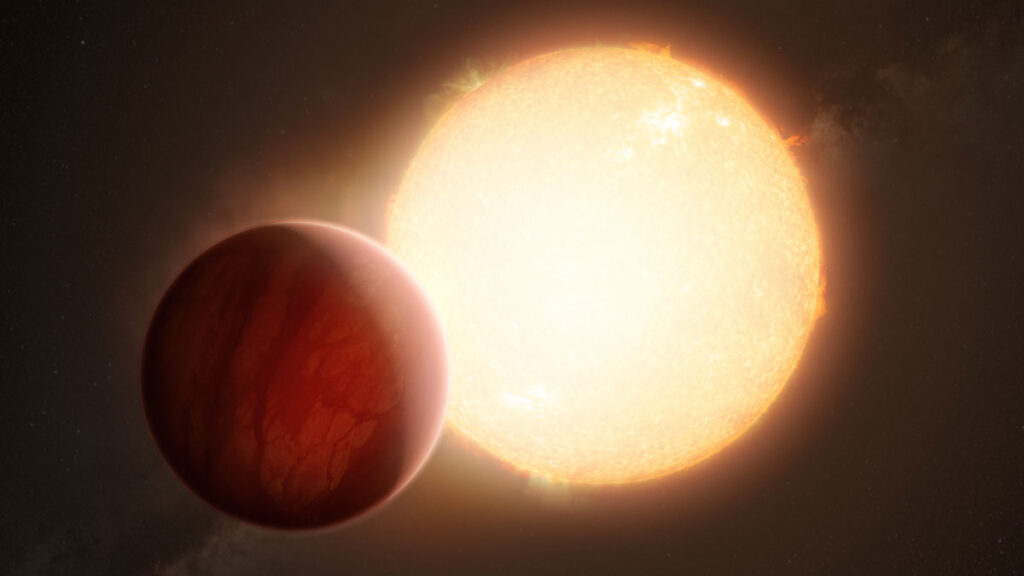

Our Sun is about halfway through its life, which means Earth is as well. After a star exhausts its hydrogen nuclear fuel, its diameter expands more than a hundredfold, engulfing any unlucky planets in close orbits. That day is at least 5 billion years off for our solar system, but scientists have spotted a possible preview of our world’s fate.

Elderly stars just get hungry.

Using data from the TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) observatory, astronomers Edward Bryant of the University of Warwick and Vincent Van Eylen of University College London compared systems with stars in the main sequence of their lifetimes—fusing hydrogen, like the Sun—with post–main sequence stars closer to the end of their lifetimes, both with and without planets.

“We saw that these planets are getting rarer [as stars age],” Bryant said. In other words, planets are disappearing as their host stars grow old. The comparison between planetary systems with younger and older stars makes it clear that the discrepancy does not stem from the fact that the planets weren’t there in the first place: Elderly stars just get hungry.

“We’re fairly confident that it’s not due to a formation effect,” Bryant explained, “because we don’t see large differences in the mass and [chemical composition] of these stars versus the main sequence star populations.”

Complete engulfment isn’t the only way giant stars can obliterate planets. As they grow, giant stars also exert increasingly larger tidal forces on their satellites that make their orbits decay, strip them of their atmospheres, and can even tear them apart completely. The orbital decay aspect is potentially measurable, and this is the effect Bryant and Van Eylen considered in their model for how planets die.

“We’re looking at how common planets are around different types of stars, with number of planets per star,” Bryant said. Bryant and Van Eylen identified 456,941 post–main sequence stars in TESS data and, from those, found 130 planets and planet candidates with close-in orbits. “The fraction [of stars with planets] gets significantly lower for all stars and shorter-period planets, which is very much in line with the predictions from the theory that tidal decay becomes very strong as these stars evolved.”

Astronomers use TESS to find exoplanets by looking for the diminishment in light as they pass in front of their host stars, a miniature eclipse known as a transit. As with any exoplanet detection method, transits are best suited to large, Jupiter-sized planets in relatively small orbits lasting less than half of an Earth year, sometimes much less. So these solar systems aren’t much like ours in that respect. Studying planets orbiting post–main sequence stars poses additional challenges.

“If you have the same size planet but a larger star, you have a smaller transit,” Bryant said. “That makes it harder to find these systems because the signals are much shallower.”

However, though the stars in the sample data have a much greater surface area, they are comparable in mass to the Sun, and that’s what matters most, the researchers said. A star with the same mass as the Sun will go through the same life stages and die the same way, and that similarity is what helps reveal our solar system’s future.

“The processes that take place once the star evolves [past main sequence] can tell us about the interaction between planets and host star,” said Sabine Reffert, an astronomer at Universität Heidelberg who was not involved in the study. “We had never seen this kind of difference in planet occurrence rates between [main sequence] and giants before because we did not have enough planets to statistically see this difference before. It’s a very promising approach.”

Planets: Part of a Balanced Stellar Breakfast

Exoplanet science is one of astronomy’s biggest successes in the modern era: Since the first exoplanet discovery 30 years ago, astronomers have confirmed more than 6,000 planets and identified many more candidates for follow-up observations. At the same time, the work can be challenging when it comes to planets orbiting post–main sequence stars.

One tricky aspect of this work is related to the age of the stars, which formed billions of years before our Sun. Older stars have a lower abundance of chemical elements heavier than helium, a measure astronomers call “metallicity.” Observations have found a correlation between high metallicity and exoplanet abundance.

“A small difference in metallicity…could potentially double the occurrence rate.”

“A small difference in metallicity…could potentially double the occurrence rate,” Reffert said, stressing that the general conclusions from the article would hold but the details would need to be refined with better metallicity data.

Future observations to measure metallicity using spectra, along with star and planet mass, would improve the model. In addition, the European Space Agency’s Plato Mission, slated to launch in December 2026, will add more sensitive data to the TESS observations.

Earth’s fiery fate is a long way in the future, but researchers have made a big step toward understanding how dying stars might eat their planets. With more TESS and Plato data, we might even glimpse the minute orbital changes that indicate a planet spiraling to its doom—a grim end for that world but a wonderful discovery for our understanding of the coevolution of planets and their host stars.

—Matthew R. Francis (@BowlerHatScience.org), Science Writer

Citation: Francis, M. R. (2025), Planet-eating stars hint at Earth’s ultimate fate, Eos, 106, https://doi.org/10.1029/2025EO250448. Published on 2 December 2025.

Text © 2025. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.